Walter Nichols: Veteran of the Month | October 2021

Walter “Wally” Nichols was born in December of 1949. He grew up in University City, MO, as the youngest of eight children, four boys, and four girls. His dad committed suicide before his first birthday, and his mom worked hard as a waitress to make ends meet. Nichols attended catholic school for nine years before going to the public high school. He remembered growing up with a fascination for the military and loved watching war movies with John Wayne. He enjoyed playing baseball and spending summers in Minnesota with his oldest sister before he started working himself at 15. Nichols worked as a curb boy for Steak n Shake and even saved up $200 to buy a 1957 Ford for his first car. Nichols stated, “I had fun in my teenage years, and it was just a different time back then.” He even recalled how a manager had asked him to start a fight with a customer while he was still on the clock. He stated with a chuckle, “I got the best of him, though.”

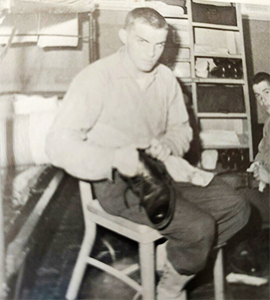

Nichols at Naval Station Great Lakes

Nichols confessed, “I wanted to be a marine all my life, but by the time I graduated high school, I had already lost two friends to the war, both marines.” He went on to say, “The country had started to turn against the war, and I figured I didn’t want to die so I thought I would enlist in the Navy, and I could sit out off the coast out of harm’s way, but it didn’t end up that way for me.”

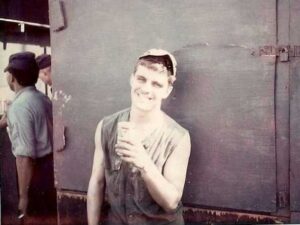

Mekong Delta 1969

After Nichols enlisted in September of 1968, he went to Naval Station Great Lakes near Chicago, IL. When he arrived, they had just changed basic training from 13 weeks to 7 weeks, and he never even saw a rifle range during basic training. Nichols commented, “It was like a boy scout camp.” He wanted to be trained as an electrician but was sent straight to the USS Carter Hall, an LSD3 or landing ship dock for the U.S. Navy. After doing one menial job after another for a few months, orders came in for a fellow seaman to go in-country to the Mekong Delta Mobile Riverine Force, but he didn’t want to go, so they sent Nichols. The Mobile Riverine Force was a marriage of a U.S. Army infantry brigade and a U.S. Navy task force. Nichols explained, “We supported the 9th infantry division, and we were a floating mash unit.” Together the two units fought the Viet Cong on the rivers and canals. “The first night I got to Saigon, they put me on a rooftop with an M16 and a helmet, and I had never been trained to fire one.” He continued in detail, “I ducked behind sandbags with shots ringing out all night, and the sky just lit up like fireworks. I never fired a shot that night and didn’t know what would happen if I tried.” Nichols recalled, “I sat ducked behind those sandbags all night worrying someone was going to come up behind me and slit my throat. It was scary.” Nichols explained how it was a shelled-out building that they jokingly called the Annapolis Hotel, which ended up getting blown apart when the Vietnamese threw a satchel bomb inside.

Nichols leaning on a 50 caliber machine gun in 1969 in the Mekong Delta

Nichols was ordered to go to the Mekong Delta River from Saigon, but when they tried to land at Dong Tam’s airbase, the airstrip had been mortared. So instead of landing at the base, the group of soldiers, a mix of about a dozen Army and Navy flying in an old WWII C 110 airplane, were taken to a landing strip in the middle of the jungle without a weapon. The soldiers were told a truck would come to pick you up, and the plane left without another human insight. A truck drove out of the jungle with a bunch of old dirty M16’s lying in the bed of the truck. Nichols said, “The driver told us to pick one up and put a clip in it because the road between here and the river is not too nice.”

Nichols made it to the river without major incident. However, they put him in the engine gang working on diesel engines once he got there, which he had never done before. “We sat in the river next to the Tango boats and the Monitors,” recalled Nichols. Tango and Monitor boats were modified from the Mechanized Landing Craft or LCM, which were primarily used to transport cargo or personnel. Tango boats were Armored Troop Carriers used for riverine patrol missions. The Monitor boat was a highly modified version of the LCM-6 used as a mobile riverine assault boat during the Vietnam War. Nichols recounted the six months he spent at Dong Tam, stating, “We pounded the shoreline with 40 MM Anti-Aircraft guns 24 hours a day, and the base at Dong Tam came under rocket fire every night.”

As Nixon started to deescalate the war and pull troops out of Vietnam, the 9th Infantry Division that Nichols unit supported was the first to go. His unit sailed back to Long Beach, CA, on the USS Nueces APB 40, before receiving his next orders for the USS Okinawa. The USS Okinawa LPH3 was an assault ship that carried helicopters and marines to be dropped off in the jungle. Nichols’ time on the Okinawa, while sitting off the coast of Danang, was non-combat.

Nichols earned the Combat Action Ribbon (CAR) for his time in the Mekong Delta. The CAR is an award for Navy and Marine Corps personnel who render satisfactory performance under enemy fire while actively participating in a ground or surface engagement. His unit also received the Presidential Unit Citation and the Medal for Gallantry. The Presidential Unit Citation is for extraordinary heroism in action against an armed enemy. The Medal for Gallantry is awarded to military personnel for acts of gallantry in action in hazardous circumstances.

Nichols made stops during his two tours in Japan, the Philippines, and New Zealand. His carrier delivered six jets to the New Zealand Air Force when he had his first experience with antiwar protesters who threw rocks at them, spit on them, and told them to take their war machines home.

After two years of service, Nichols was honorably discharged as an E3 on October 1st, 1970. His early discharge was due to hardship because his mother needed him home to take care of her. But, Nichols said, “I came home in one piece.”

In 1975 Nichols met his future wife at a bible study at the community college. They were married in 1977 and had three children, two girls, and a boy. Nichols also had a son from a prior relationship. After retiring twice from Pitney Bowes, Nichols decided to take a sales position part-time. A year later, he was working full-time again and continued to do that for another 17 years. Unfortunately, in 2016 he lost his daughter Rachel to breast cancer. Nichols currently has eight grandchildren and one great-granddaughter.

Nichols and friends saluting the 13 at the VFW

Now, fully retired Nichols likes to spend his time with friends at the VFW. Even though he is not a fan of politics, he has held three different positions at the VFW. He was Junior Vice for a year and Senior Vice for a few months before the Commander had to step down, and he was automatically promoted to Commander. Nichols expressed how the VFW has been instrumental in his life after having a heart attack due to agent orange and suffering from PTSD.

Nichols on his 70th birthday

Nichols stated, “I had an attitude when I first joined, the way boot camp went and the way they treated me sending me directly in country with no training I didn’t enjoy. But, I did like being in country more than on the carrier. I did enjoy the camaraderie with the guys in a combat zone and getting to travel and see some of the world at 19 and 20 years old.” He went on to say, “I am proud of my service in Vietnam, and I support veterans.”

Veterans Care Coordination is proud to recognize Wally Nichols for his service to our country. We are privileged to have the opportunity to share the stories of our nation’s heroes. Thank you for your service, Wally Nichols, and welcome home.