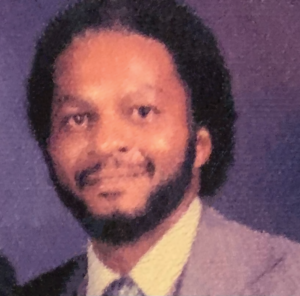

Dwight Henry: Veteran of the Month | September 2023

Dwight Henry, born in May 1950, was the middle child among seven siblings. His upbringing in Jackson, Mississippi, unfolded against a tumultuous era for African Americans. Yet, he was unwavering in his commitment to pursuing a peaceful path. Henry grew up loving music and had an early sense of responsibility. He started assisting with babysitting, diaper-changing, and household chores at an early age, displaying a sense of maturity beyond his years.

His father, employed by the railroad, was granted one free pass per family member each year to go anywhere the train traveled. This pass allowed young Henry to take a remarkable journey, a solo train ride to Chicago at nine years old to visit his aunt. Henry remembered, “We had to grow up real fast, and we were really responsible at that time. It was exciting, and I got hooked on trains.” His mom and grandma packed him lunch in a brown paper bag, fueling his adventure. The following year, he repeated the journey, this time accompanied by his younger eight-year-old brother when he was just ten.

As Henry entered high school, his affinity for music flourished as he earned state honors playing the French horn. In addition to music, he was also a member of the tennis team, but music was always his true passion. Henry shared, “I loved music! I could do Mozart backward and forward.”

A pivotal moment occurred during high school when he and his best friend decided to enroll in a typing class. Henry stated, “That’s where all the pretty girls were, but they gave us such a hard time it was embarrassing.” Despite initial teasing from their female classmates and being told they wouldn’t be any good at it, Henry and his friend mastered the art of typing. Henry recalled, “That caused me to buckle down and learn how to type really well.” They became the top two typists in school, effortlessly typing 100 words per minute without errors.

Henry’s life took an unexpected turn the summer before his sophomore year when his mother met a woman who arranged for him to work at an exclusive international New Hampshire summer camp. Henry had access to all camp activities in exchange for working in the kitchen. He continued to work there for three summers during high school, earning a position as a counselor by his second summer. The experience was transformative, exposing him to a global community of students and expanding his horizons. Henry explained, “I had access to swimming, sailing, karate, archery, horseback riding, all of those things, and that really changed my life because during that period of time, there were issues, and Martin Luther had been killed, and I had a choice of whether or not to go bitter or stay with Martin Luther practices, and summer camp gave me perspective and kept me on the Martin Luther path of peacefulness.” Henry continued, “That was one of the things that changed my life and showed me that not all white people were bad because it was rough down here in Mississippi in the 50s and 60s. Trust me.”

Through hard work and determination, Henry secured a music scholarship to Jackson State while maintaining a stellar academic performance. In 1968, Henry embarked on his first semester of college, only to encounter financial setbacks due to the school’s involvement in a scandal regarding athlete payments. Consequently, Henry lost his music scholarship and needed to work full-time. His exceptional typing skills quickly secured him a position at Western Union, where he spent four fulfilling months until he received a draft notice from the United States Army. Knowing he wanted to avoid following his older brother’s path as an Army paratrooper in Vietnam, Henry headed to the Naval recruiting office to enlist.

Following boot camp, Henry was stationed in Pensacola, Florida. Henry said, “They did a security check on me, and I had a top-secret security clearance, so they put me in a course to be a cryptographer.” A cryptographer writes (or cracks) the encryption code used for data security. His sharp skills in speed and accuracy propelled him to the top of his class. Henry explained, “My typing course came through again. I came in number one in the class and got my choice of duty station.” After hearing his choices, he decided on Scotland. Henry detailed, “It was an old retired military base, and that is all they did there was security stuff, and I loved Scotland. It was a wonderful time.” He relished his time in Scotland, where he was treated with the respect he deserved, forging friendships and earning a high-security clearance.

Dwight Henry

Upon his discharge, Henry spent two months in Japan before returning to Pensacola. His love for music led him to entertain the base with his extensive vinyl collection, earning him the title of Sailor of the Month. Eventually, in 1972, he left the Navy as an E4, despite their desire for him to stay, eager to embark on the next chapter of his life. Reflecting on his military service during the Vietnam War era, he remarked, “I was ready to get out. It was horrible being in the military during the Vietnam War.”

Now 21 years old, Dwight decided to return to the beloved New Hampshire summer camp as a staff member. His outstanding academic record and Veteran status quickly earned him a scholarship for a New England school, which he supplemented with his VA benefits under the GI Bill. Henry found learning how to learn was the key to academic success, and he completed his degree in just three years. His educational journey even took him to Arundel, Sussex, England, where he spent a year studying abroad at the college’s sister school. Henry recalled, “I loved it there. Every weekend, we would go off and visit another country.”

Henry at the farmers market June 2023

Henry’s parents celebrated his college graduation with their first road trip together, driving to New Hampshire for the occasion. After a brief stint in Mississippi, he spent the next three decades in Denver, Colorado. He started a new career teaching vocational skills to people with disabilities, followed by a successful stint as a car salesman for over ten years. His commitment to honesty and a touch of humor earned him the sales manager position within six months of starting the job.

Driven by his passion for helping others, Dwight established his own Senior Coop Services business dedicated to assisting senior citizens. He bought his first computer, a truck, and lawn care equipment, but he planned to be more than a landscaper. He used his educational background to build a business model involving a network of vendors providing different services, similar to Angie’s List. Then Henry figured out a way to have localized customers, cutting down on travel and increasing profits for everyone.

By the late 1990s, he sold his business to start a new adventure in technology. He taught himself how to write database applications and started a new business where he developed and sold software. He was at the forefront of web development, creating multiple websites that offered different services, some of which remain active today.

Dwight Henry at the 100 Black Men Fellowship in December 2020.

As he reached 55 years old, Henry’s health began to decline due to genetic factors. Initially, he was reluctant to seek assistance from the VA when a friend tried to convince him to go. He didn’t think he deserved help, stating, “I didn’t feel as though I deserved the VA. I thought that was for Veterans that were hurt in the war. They needed help more than me.” Henry knew how badly other Veterans were hurt during Vietnam as he lost his older brother ten years ago from an illness related to Agent Orange. Henry recalled, “I knew what my brother went through and hearing stories of what others went through, and I took some of those bad things with me and didn’t give the VA a chance.” Eventually, he went to the VA hospital, but by then, his health was so bad that a friend had to help him walk into the building. He soon embarked on a year-long recovery journey under medical supervision. Henry said, “I finally became proactive and listened to the doctor, and that is why I am alive today.”

Though never married, Henry’s life took a poignant turn in 1972 when he fathered a child with a girlfriend who placed the baby boy for adoption. His mother’s best friend adopted the child, and Henry visited him every chance he could. He never wanted his son to know he was his birth father and secretly helped his son’s parents do anything he could for him. Tragically, his son passed away at the age of 39 due to heart failure. Henry stated, “I guess I passed on my poor genetics. But he had a good life and good parents, and I couldn’t ask for more.”

When asked what his biggest takeaway was from the military, Henry emphasized the importance of discipline and trust, stating, “The biggest thing I learned was discipline. It wasn’t too much of a strain because of how we were raised. Church on Sunday, shine your shoes on Saturday. But there was a brotherhood. There was a trust. You had to trust other people.” Reflecting on his military service, Henry emphasized the critical role these values played in safeguarding the lives of his fellow soldiers, explaining, “There is a reason for that discipline. Things had to be right because people’s lives were at stake. I had to be accurate and fast. You rely on the person covering your back.”

Henry’s unwavering commitment to integrity, self-improvement, and positive and peaceful attitude defined his life journey, guiding him through diverse experiences and meaningful contributions to his community and the world.

Veterans Care Coordination is proud to recognize Dwight Henry for his service to our country. We are privileged to have the opportunity to share the stories of our nation’s heroes. Thank you for your service, Dwight, and welcome home.