Leon Schell: Veteran of the Month | January 2024

Robert Leon Schell was born in the heart of Louisville, Kentucky, in 1927. He preferred to go by Leon, as his mother never wanted him to be called Bobby. Schell had an older sister with whom he shared a very close bond. His father worked at a woodworking plant that, at one point, produced wooden frames for Ford automobiles. Schell’s mother was a homemaker, and Schell laughed, “This is funny, but my dad never signed his own paycheck his whole life that he was married. Mother was good at the financing, and she only went to school till the eighth grade and she ran the family.”

Robert Leon Schell was born in the heart of Louisville, Kentucky, in 1927. He preferred to go by Leon, as his mother never wanted him to be called Bobby. Schell had an older sister with whom he shared a very close bond. His father worked at a woodworking plant that, at one point, produced wooden frames for Ford automobiles. Schell’s mother was a homemaker, and Schell laughed, “This is funny, but my dad never signed his own paycheck his whole life that he was married. Mother was good at the financing, and she only went to school till the eighth grade and she ran the family.”

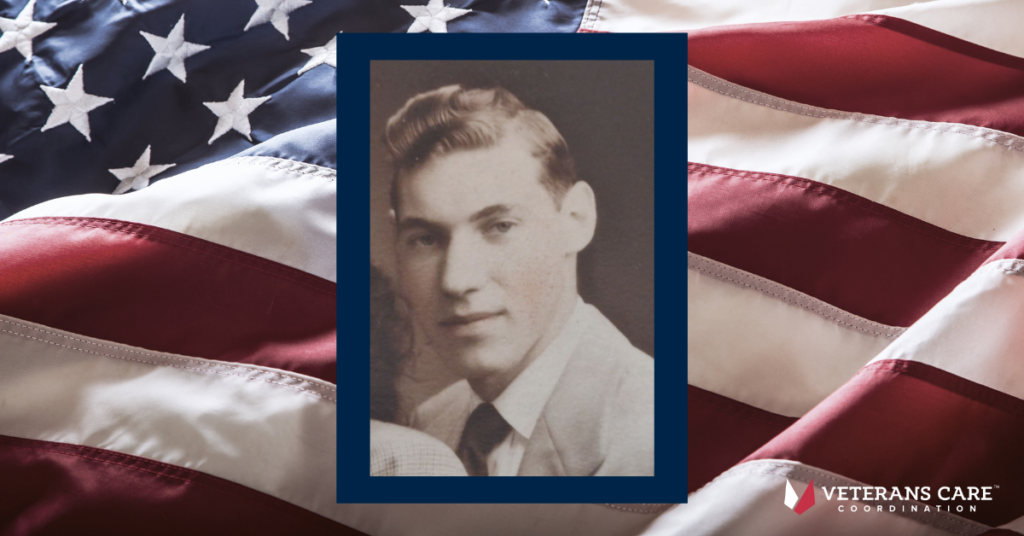

Schell as a young boy top left.

Schell reminisced as he shared childhood memories of growing up in the city. He proudly described his street, Confederate Place, as a dead-end street that stretched three blocks long. His house was the second one from the end, close to the train tracks and depot. Living at the end of a dead-end street allowed them to enjoy a game of kick the can out in front of his home with friends. Triangle Park was situated next to his house, where he played with the kids in the neighborhood as he grew up. In the summertime, recreational directors came to set up events in the park. Schell recalled with a chuckle, “One thing that I remember the most is at night, they had a storyteller called Johnny the Storyteller, and at nighttime, he would come to tell us these ghost stories and scare the devil out of us.” He went on to say happily, “I had a good upbringing like that.”

In 1937, a flood resulted in water being pumped out of the viaduct and onto his street. Schell recalled, “They sent a moving van down in the water and said, ‘Everybody get out; if you don’t get out now, you can’t get out.'” The Schell family grabbed what they could and climbed into the van. They were taken to a farm till the flood waters cleared. Even while staying on a farm, Schell recalls how, despite the difficult circumstances, it didn’t stop his father from caring for the family, “He somehow got over the tracks and went to work every day.” Schell was only ten years old at the time. He doesn’t recall how long they had to stay there but definitely remembered one thing: the outhouse. Schell laughed as he said, “They had outhouses, and I had never experienced an outhouse before.” Fortunately, their home was not affected by the flood, but it came close as the water rose to just an inch below the entrance.

Schell with family at his grandsons USMC graduation.

During high school, Schell took part in the ROTC program. He graduated high school in 1945, but in February of his senior year, at age 17, he joined the Navy Reserves. Once he graduated and turned 18, he was sent to boot camp in Sampson, New York, instead of Great Lakes Naval Base due to an epidemic. Upon completion of boot camp, the recruits were informed that if they wished to serve on a ship, they would have to sign up for a minimum of six years with the US Navy. However, this requirement did not align with Schell’s future plans. As a result, he was assigned to undergo training in ammunition handling school at Camp Peary, close to Williamsburg, Virginia. His job was to unload the ammunition and store it in bunkers when the ships returned from a mission, which could be very dangerous. Schell sadly explained, “While I was there, of course, I was bartending at the time; one of the sailors accidentally hit the shell against the bulkhead and blew the ship up. Everyone was just beside themselves over it.”

Schell on left with his hiking club.

Schell spent time in Earl, NJ, where he bartended at the VOQ or the officer’s quarters before transferring to Dover, NJ, located 50 miles from New York. Schell and his fellow sailors were allowed to visit the city on weekends, and one of their favorite spots was the Coca-Cola Canteen on 42nd Street. Schell described, “We could go in there and get tickets to any shows they had on Broadway, and it didn’t cost us anything; we could go to as many shows as we want.” According to Schell, his favorite show was the one featuring the Rockettes. He explained how service members didn’t have to worry about lodging expenses while in the city either and expressed how much he enjoyed visiting the city and seeing Broadway shows. Even though Schell was in the Navy, he was never aboard a ship. He was considered a “dry land sailor” and explained that the closest he ever came to being on a ship was during a tugboat strike in New York.

Schell and his grandson.

Schell’s time in the service as a Reservist ended with the conclusion of WWII. Reservists only serve during wartime. Following an honorable discharge, Schell returned home and enrolled at the University of Louisville. The university was situated behind Triangle Park, just across the street from his childhood home. He moved home with his parents and attended school during the day for two years but had to complete his last two years at night school after getting married in 1950. Eventually, the University of Louisville purchased all the homes in the area, including his parent’s home. Now, the only remnants of his childhood home are two large maple trees that stand in what was once his front yard. Schell exclaimed, “They had all these beautiful homes, and they tore them all down instead of making fraternities or sororities out of them. It was crazy!”

In 1952, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in business management and went on to work for a printing company. Schell

Schell at 94 years old.

explained, “We did the letterpress printing for the state of Kentucky, which was on a bid contract.” Schell was also a member of the Junior Chamber of Commerce, also known as the Jaycees, even serving as a Parliamentarian. The Jaycees at that time he was a member provided leadership training and development programs for young people aged 25 to 36. He fondly talked about how he enjoyed traveling to different conventions. He was even made an honorary member of the Michigan Jaycees in 1963 and was the first person outside of the state to be a member. He worked as a director and secretary during his time with the Jaycees.

In 1973, Schell and two partners started their own printing company in Scottsburg, IN, about 30 miles north of Louisville. They specialized in producing desk calendars for small five-and-dime stores. However, when Walmart emerged and outcompeted the smaller businesses, Schell decided to retire. He closed down his printing company in 1989 and retired at age 62.

After retiring, Schell, who had served as a deacon for over 20 years, became even more active in his local Walnut Street Baptist church. Schell volunteered at the church every weekday, working five days a week to support the church’s activities. In 1981, following his divorce, he began creating a newsletter for the 275 singles who attended his church. Despite having no prior experience with computers, he eagerly learned the technology and found it to be a great source of joy. Additionally, he was given a laser printer by a church member, and he used it to create both the church bulletin and the newsletter. He stated, “I really enjoyed the desktop publishing.” Schell continued volunteering at the church from 1981 until the pandemic struck, saying, “I can’t go down there anymore, but I really enjoyed it when I could.”

Schell and his sister.

Schell has four children, three daughters and one son, who are all retired now. He has six grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren. His son went into the military in the Army and was stationed in Germany. He has a grandson in the Marines who served in Afghanistan for two tours, almost being fatally injured twice in combat. His sister had been living across the street from him since 1985 until she passed away in 2019. While fondly reminiscing about his life and past, Schell stated, “I think I lived in the best of times. I had a great upbringing and a good life.”

Veterans Care Coordination is proud to recognize Leon Schell for his service to our country. We are privileged to have the opportunity to share the stories of our nation’s heroes. Thank you for your service, Leon.