Greg Hendricks: Veteran of the Month | May 2023

Greg Hendricks was born in St. Louis County in 1950 and raised in St. Charles, MO, just west of the Missouri River. He was the second oldest of four boys. Hendricks stated, “I consider myself a homegrown tomato. I don’t know anything but St. Charles.” Growing up, Hendricks loved all sports but had a passion for baseball which he started playing at eight years old. Unfortunately, life at home wasn’t always easy. He was the only stepson of the four boys, and his stepfather, who was also a war veteran, was abusive to Hendricks and his mother.

Hendricks continued to play baseball through his senior year of high school and was offered a baseball scholarship to Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. However, his joy of the scholarship was short-lived as he received a lottery number from the U.S. draft. Hendricks said, “I had a chance to go to college to play baseball, but instead, I went to Vietnam.”

During Vietnam, young American men were being involuntarily drafted through a lottery. Men between 18-26 years old were given a number between 1 and 366, which corresponded with their birthdays. The lower numbers were called first, and Hendricks explained, “My lottery number was number 5, and I knew right away I would go to Vietnam.” However, a recruiter explained that his chances of not going to Vietnam would be better, or he could choose his path by volunteering. Since Hendricks wasn’t already enrolled in classes, he didn’t qualify for a college deferment, so he went down to volunteer. Hendricks said, “I volunteered for the draft on the promise that my chances of going to Vietnam would not be very high. Which we know now wasn’t what happened.”

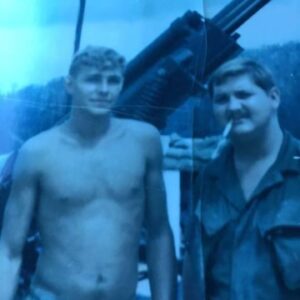

Hendricks and a friend in the A Shau Valley looking over Hamburger Hill during a fire mission in 1969.

Soon Hendricks found himself in basic training at Fort Leonard Wood, MO. After basic combat training, the newly enlisted Army recruits would be given their Military Occupational Specialty or MOS for Advanced Individualized Training or AIT. Hendricks MOS was 11 Bravo 11 Charlie, and he explained, “11 Bravo was infantry, and the 11 Charlie was mortar platoon.” He continued to explain that the mortar platoon consisted of training on short-range armor artillery stating, “Actually, you’re trained in, as an infantryman and as a mortar person in a mortar platoon, where you’re providing support to ground troops around you with mortar fire, close range.” Hendricks was also trained on a PRC 25 radio. Army Gen. Creighton Abrams, who commanded military operations in Vietnam from 1968 to 1972, called the radio, also known as the Prick 25, “the single most important tactical field item in Vietnam.” The radio operator was also considered a high-priority target by the enemy. Hendricks described, “You carried the radio pack on your back out in the field and called in enemy movement, you could call in medevac, anything else like that.”

Hendricks spent approximately six weeks in Fort Sill, OK, for AIT and another six weeks in Fort Knox, KY, for radio school before his training in the States was complete. Without getting any leave to visit family after training, Hendricks was sent to Fort Dix, NJ, where he would depart for a 30-day stay in Germany before being shipped to Vietnam.

At 18 years old, Hendricks landed in Bien-Hoa and was transported to Long Binh, a former U.S. Army base in South Vietnam right outside of Saigon. From there, he was assigned to his replacement center or base camp in Chu Lai. Hendricks stated, “You are just along for the ride until you finally get to your post.”

Once in Chu Lai, Hendricks’ first responsibility was relieving the radioman. He was sent out into the field and would relay messages on enemy movement back to a radio relay station on base. Unfortunately, his unit was eventually attached to the 101st Airborne Division in Hue, which moved him to the A Shau Valley. The 25-mile-long valley was used to funnel troops and supplies from Hue and Danang and was an arm of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. It is also the location of a violent and controversial battle on Hill 937, or “Hamburger Hill.” Hendricks noted, “It was not a good place to be.” He said, “We tried for 13 days to take that hill and after we took it, to give it right back to the V.C.; we lost, I don’t know how many, it was just devastating. I had 25 soldiers in my platoon, and me and six others were the only ones to come home.” The memory of what happened during his time on Hill 937 haunts Hendricks as he continued to explain, “Hamburger Hill was named that by the G.I.s and the meat grinder we went through while we were there. On the 11th day, we made it to the top of the hill, and on the 13th day, they gave it right back to the V.C., saying there was no strategic benefit for us to hold that hill.” The contentious battle drew much criticism at home after images were published in Life magazine, only further dividing the country, and in 1987, a Hollywood depiction of the battle was released. Hendricks said, “I was still only 18 years old then, and when I got to Vietnam, I was gungho and thought we were going to make a difference, and we wanted to turn the lives around for the people in South Vietnam and the longer we were in battle or around battle and the devastation that we witnessed, my attitude started to turn, about six months into Vietnam.” He continued stating, “What are we doing here? The people don’t want us here. You just start thinking, why are we doing this when we are not supported at home, and we are not supported over here? Your attitude starts to change.”

Hendricks spent nine months and 27 days in Vietnam, including his 19th birthday, before getting severely injured in the A Shau Valley. Hendricks disclosed, “All I can say is, let’s put it this way, I caught some bad incoming rounds and took a lot of shrapnel in my back and my legs. There is a lot more detail than that, but I don’t feel comfortable talking about it.” He was medevaced out to Cam Ranh Bay, where he spent 30 days in the hospital before being stable enough to be transported to a hospital in Germany and then later to Carson City, CO. Altogether, spending 75 days total in a hospital healing from his injuries.

Hendricks on vacation in Arizona a few years ago.

In January of 1970, Hendricks was honorably discharged and started on a downward spiral stemming from the atrocities he had seen in Vietnam. He had survived the war, but the trauma of what he had seen left invisible scars that ran deeper than the physical scars he had endured. Hendricks had post-traumatic stress disorder. A condition that can last years and causes anxiety, nightmares, and flashbacks triggered by a traumatic event. Hendricks admitted, “You feel blessed that you’re coming home alive, but you’re still damaged goods. You have an invisible disability.” The strain he was under took its toll, and Hendricks started drinking heavily to numb himself from the memories he couldn’t escape. Hendricks stated, “I drank—a lot. Ran. Hid. We come home, and we are just kinda lost. Like purgatory, we are just out there.”

As hard as it was trying to adjust to civilian life, Hendricks eventually got a job in his hometown through a Public Employment Program (PEP) appraising houses through the county assessor’s office. There, a fellow employee, Sandy, walked over, introduced herself, and pointed out that he had two different colored socks on. He asked her out, and by the end of the date, he had professed that he would marry her, and he did. The young couple married in 1973 and eventually had a daughter, Amber.

Now a husband and father, Hendricks’ struggle with PTSD continued, and he said, “Mainly, I drank to forget.” As hard as he would try to push through, it was a constant battle, and drinking was his temporary fix to numb the pain. He would isolate himself and avoid large groups or gatherings, and the more he drank, the worse things got. Hendricks, who loved baseball, couldn’t bring himself to go to a game. As supportive as his wife was over the years, it affected their relationship. Hendricks disclosed, “I was going to lose my wife and my daughter. I was going to lose them.”

One evening while having too many drinks in a bar, Hendricks was fortunate enough to meet a man, another Vietnam Veteran, only he wasn’t drinking. The man asked Hendricks to take a ride with him that night, and Hendricks admitted, “I only got in with him because he was a Marine and a Vietnam Veteran. I didn’t know where he was taking me.” When they got in the car to leave, Hendricks started on a journey that would change his life forever. He described, “I walked into a room, and there was a group of chairs in a circle, and I didn’t know where I was.” The stranger from the bar brought Hendricks to the Vet Center in downtown St. Louis. The man explained, “We are all Vietnam Veterans, and we are here to save your life.” At first, Hendricks resisted and tried to walk out, stating, “I told him I don’t want to sit here and talk about my trauma, and I don’t want to take your traumas home with me. But I can say that was the best thing that ever happened to me. I felt welcomed again, and I didn’t have to hide from them. They were me.”

That fateful night meeting a stranger in a bar led Hendricks on a journey to heal. Hendricks hasn’t touched alcohol in 35 years. Although it hasn’t always been easy, Hendricks has stayed determined. He continues to see a psychiatrist specializing in PTSD, but that isn’t the only thing he has endured from his time in Vietnam. Hendricks disclosed, “I am 100% disabled with PTSD. Lost almost all my hearing from the artillery, and I had stomach cancer with agent orange.” Hendricks has been entirely disabled since 2008. When asked if he had earned any medals in Vietnam, Hendricks sighed and said, “I did. I didn’t want ’em, but I did. To me, it is just a reminder of what I went through.” Although he could barely bring himself to say, Hendricks quietly admitted he was awarded a “P.H.” (Purple Heart) and a “B.S.” (Bronze Star.)

Hendricks still has triggers and will never forget the horrors of war. His wife has supported him through their 49 years of marriage, and Hendricks states thankfully, “She is a very good wife, good mother, and she probably should’ve divorced me years ago, but she stood by me. She doesn’t fully understand exactly what I went through over there.” Hendricks went on to say, “My daughter is a school teacher who teaches gifted students. We have become closer over the years, but it was a tough go. I wasn’t around for her. I was still in that running phase when she was born, and I wasn’t there for her. I was looking for myself instead of spending time with her, but we have gotten better. I love her very much, and she is a good kid.”

Currently, Hendricks goes to the gym daily and works with a trainer certified in PTSD three times a week, admitting, “It’s my PTSD relief. It takes care of my stress and puts me in a different frame of mind. I use the exercise to keep my health up, and it works.” He admits that even with all he went through in Vietnam, he enjoyed his time in the Army before the war, stating, “If it wasn’t for Vietnam, I would’ve made a career out of the Army. I liked the military life, the perfection, the discipline, always being STRAC, which means looking sharp and feeling sharp. I always enjoyed that until I went to Vietnam.”

Veterans Care Coordination is proud to recognize Greg Hendricks for his service to our country. We are privileged to have the opportunity to share the stories of our nation’s heroes. Thank you for your service, Greg, and welcome home.

Sources:

https://www.historynet.com/vietnam-an-prc-25-radio/

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/paratroopers-battle-for-hamburger-hill