Susan Hubbard Rudd: Veteran of the Month | January 2021

Susan Hubbard Rudd was born on June 23, 1918, in a log cabin in Idaho, on a farm her father received through the Homestead Act. She was the second oldest of three children Her mother was alone in the log cabin during childbirth while her father was in town trying to locate the doctor. Rudd’s mother decided she didn’t want to stay in Idaho. Being the determined independent women she was, a trait she passed down to Rudd, she did something rare for that time, she left her husband and moved with her children to New York state. Living just south of Lake Ontario, Rudd learned to swim in the lake’s frigid yet pristine water. Rudd’s mother worked as a traveling salesperson and was as talented as any man in her industry, if not more so. Due to her job, the family ended up living in several different areas, such as Buffalo & Niagara Falls, before settling in Cleveland, OH. Rudd graduated from high school in 1936. After graduation, Rudd spent two years in night school at the John Huntington Institute learning architecture. She also volunteered as an air raid warden. Wardens were used to alert the public in the event of an attack on US soil.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Rudd knew she wanted to join the military, but her mother was against it. Being more scared of going against her mother than joining the military, Rudd hatched a plan with her best friend, Roselle Graham. The determined girls told each of their mothers they were spending the night at the others house. Instead, they traveled to Columbus, OH, to enlist in March of 1943. They chose to enlist in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) on the promise that they would keep the girls together. WAAC was established to work with the Army “for the purpose of making available to the national defense the knowledge, skill, and special training of the women of the nation.” Members of WAAC were given official status and salary but weren’t considered part of the Army. Once the girls returned home from Columbus, they had to confess to what they did, but it was too late for their mothers to do anything about it.

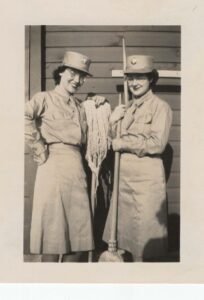

Susan Rudd (right) with Roselle Graham.

The girls were sent to Daytona Beach, FL, for training in stock supply. Even though they were promised to be kept together, Rudd was sent to Lemoore Army Airfield in Lemoore, CA, and Roselle was sent to Boston. Without her best friend, Rudd boarded a train car for California. To separate the four females from the rest of the soldiers in transfer, the girls were locked in the last car on what would be a very memorable train ride. Her train had to pull off the tracks for another train to pass when part of their engine blew, killing someone on the passing train. This left the girls stranded in the desert for over 24 hours without food or water until a farmer happened to come upon them and gave them a ride to the

Basic training.

base. By then, the Army base had been looking for them, but they were denied entrance onto the base when they showed up without their paperwork.

Lemoore was a new experience for the young private. She arrived without an assignment and worked odd jobs but commented on how much she enjoyed it because it gave her the chance to meet and get to know many different people on the base. The toughest part was trying to get on and off the bicycle she rode around the base because of the tight skirts they were assigned to wear. Rudd stated, “They didn’t know what to do with us at first.” When she arrived, there were approximately eighty women on base in two barracks. Rudd was assigned to work with an architect to redesign the barracks, officers’ club, and the PX to accommodate the women on base. Her boss had been a professor at the Illinois School of Architecture and taught Rudd a lot.

Eventually advancing her rank to sergeant, Rudd became a Link trainer, which taught cadets instrument flying in simulators. Out of forty trainers, three were women. Rudd performed that job from the summer of 1944 until she was honorably discharged in 1945.

Rudd receiving her Link Trainer award

Rudd spent a total of 36 months enlisted, but only two and a half years of her time served is recognized. It wasn’t until Women’s Army Corp (WAC) was created in July 1943 that the WAAC’s were given the opportunity to stay enlisted and become a member of WAC or return home. Out of 100 women, only three chose to leave. The 97 women that stayed were finally considered Army soldiers. Upon becoming members of WAC, the base commander decided the women needed to prove themselves as soldiers. They were taken to the desert area on base for bivouac training. It is an exercise to build readiness in a learning environment. One morning as Rudd and another girl shook out the blanket they had been sleeping on, and a giant tarantula fell out.

Bivouac training.

Rudd’s fiancé was in the Marine Corps and was stationed 90 miles from her in California. Allowing them the opportunity to see each other a few times before he was shipped overseas. After being discharged from the Army, Rudd went on to marry her fiancé and start a family. Their daughter Linda was born in 1948, and their son Bruce in 1951. They lived east of Cleveland, in a house Rudd designed herself and had built. The builder admired her home so much he even offered to buy it back. While raising her children, Rudd worked at an architectural firm that designed railroad crossings. She did all the drawings on linens as she was quite the artist. She lost her husband just one month shy of their 20th wedding anniversary. He had never fully recovered from his time in World War II. After losing her husband, Rudd went to nursing school so she could provide for her children. When asked why she never married again, she said, “I found out I could do just as well by myself.” Once she completed school, she and her children moved to South Carolina to be closer to her parents. Rudd worked as a licensed practical nurse at Forsyth Medical Center and later at Medical Park Hospital. She ended her career as a nurse at The Children’s Home, a local orphanage, where she worked until she was 85 years old. Rudd stated that working with children is probably what helped keep her so young. She reminisced fondly, “The children can be so funny, so loving, and so forgiving. They were always doing something unexpected.”

Now Rudd stays busy by being active in her church. For years she taught Sunday school, worked in the daycare, and spent time in the quilting circle. In her sixty’s she started painting, a hobby she truly enjoys. Rudd even reconnected with an old friend, Maynard Fosberg. They were stationed at Lemoore together, and with Fosberg being a photographer, he had plenty of pictures of his dear friend Susan Rudd. They lost track of each other when he was transferred to Georgia, but she found him last year. Rudd exclaimed “I was really glad to hear he made it through the war without being killed” she went on to say, “I didn’t know what had happened to him.”

Rudd will be 103 years old this June and is doing very well, even recovering quickly from a broken shoulder. She is extremely proud of her time in the military, and rightly so. Rudd loves reminiscing, and her stories are fascinating. Her upbeat, happy manner is infectious and makes you want to spend the rest of the day listening to her. Rudd even wrote a book in 2019 titled Women in the Army: Memoirs from a First Generation W.A.A.C. to W.A.C. March 1943-December 1945

Veterans Care Coordination is proud to recognize Susan Hubbard Rudd for her service to our country. We are privileged to have the opportunity to share the stories of our nation’s heroes.